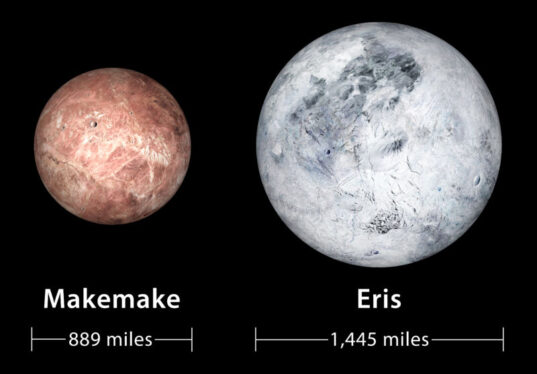

Enlarge / Artist’s conceptions of what the surfaces of two dwarf planets might look like. (credit: SWRI)

Active geology—and the large-scale chemistry it can drive—requires significant amounts of heat. Dwarf planets near the far edges of the Solar System, like Pluto and other Kuiper belt objects, formed from frigid, icy materials and have generally never transited close enough to the sun to warm up considerably. Any heat left over from their formation was likely long since lost to space.

Yet Pluto turned out to be a world rich in geological features, some of which implied ongoing resurfacing of the dwarf planet’s surface. Last week, researchers reported that the same might be true for other dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt. Indications come thanks to the capabilities of the Webb telescope, which was able to resolve differences in the hydrogen isotopes found on the chemicals that populate the surface of Eris and Makemake.

Cold and distant

Kuiper Belt objects are natives of the distant Solar System, forming far enough from the warmth of the Sun that many materials that are gasses in the inner planets—things like nitrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide—are solid ices. Many of these bodies formed far enough from the gravitational influence of the eight major planets that they have never made a trip into the warmer inner Solar System. In addition, because there was much less material that far from the Sun, most of the bodies are quite small.

Read 19 remaining paragraphs | Comments