The night Sinéad O’Connor tore up Pope John Paul II’s photo on Saturday Night Live, Daniel Glass, then head of her label, was in the studio audience. “It was silence, it was shock, it was frozen. That was the most pregnant pause of media I’ve ever been involved with,” recalls Glass, at the time president of EMI Records Group North America, which encompassed O’Connor’s label, Chrysalis Records. “I went to see Sinéad [afterward], and she was in a state. She was mumbling. It was settling in: ‘I think I just did something big, something profound.’”

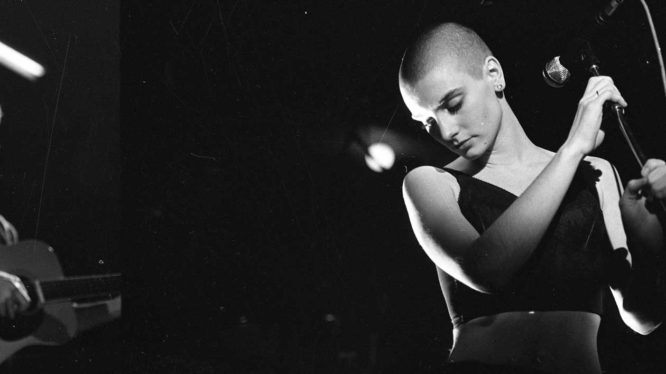

Glass, like others on O’Connor’s team, received no notice of the singer’s plan that night in 1992. She had planned to perform her song “Scarlet Ribbons,” but alerted SNL and her reps that she would tape a version of Bob Marley’s “War” at dress rehearsal instead. The photo-ripping was a surprise. “She knew exactly what she was doing, but she couldn’t tell anybody,” says Elaine Schock, then an independent publicist for O’Connor, the Irish singer, songwriter and pop star who was found dead in London Wednesday (July 26) at 56. “She wanted to make a statement, and she made that statement.”

Glass and Schock had worked with O’Connor from her earliest days as a recording artist, just before she released her Chrysalis debut, The Lion and the Cobra, in 1987. Back then, Glass was a Chrysalis promotions executive when the label signed O’Connor through a label it distributed: Ensign Records, run by the late Nigel Grainge, brother of Lucian, now chairman/CEO of Universal Music Group. The promotional challenge? Getting people to listen in the first place. “If you heard it, you would love it,” Schock says. “As soon as you put it on, you don’t take it off.”

At first, O’Connor gamely participated in publicity and gimmicks. She and Schock bonded; both were raising small children, and the singer would pick up the publicist’s daughter from nursery school. “For me, it was starting off my career as an independent publicist; for her, it was starting off her career as an artist,” Schock says. “I sent out hundreds of records to journalists and did my best to get attention.” In January 1988, the New York Times published a lengthy review.

Upon meeting O’Connor, Mike Bone, then Chrysalis’ president, blurted out that she could shave his head if The Lion sold 50,000 copies. She laughed. After it shipped 20,000 in its first week, he thought to himself, “Oh, s—, there goes my hair’” — and made good on his promise, sending out photos to reporters as a publicity stunt, as the album surged to more than 500,000 sales. “We had to get her in front of people and we did,” he says. “And it sold.”

Glass emphasized college radio stations and music journalists, and accompanied O’Connor to Canada, Buffalo, N.Y. and elsewhere for news conferences. But O’Connor threw him out of all of them. “It was her way of saying, ‘I don’t want to be part of the establishment, I don’t want to be part of the game, I don’t want to be marketed,’” says Glass, now CEO of indie Glassnote Records.

When John Sykes, an MTV co-founder, took over as president of Chrysalis in January 1990, the first song he received was O’Connor’s Prince cover “Nothing Compares 2 U.” Standard operating procedure for an “alternative” artist, as O’Connor was classified back then, would have been to release a harder-rocking track to college radio stations as the first single, then try to cross over the obvious pop hit to Top 40 stations later. But with “Nothing Compares,” recalls Sykes, today president of entertainment enterprises for iHeartMedia, “We had no choice. This song was a once-in-a-lifetime record and nothing was going to stop it.”

The hit became what Sykes calls “the biggest song in the world, virtually overnight” — lucky timing for him, but leading to a level of stardom O’Connor came to regret. In 1990, she decided not to allow “The Star-Spangled Banner” to play before her New Jersey concert, offending Frank Sinatra, who suggested he would “kick her ass.” Sykes describes O’Connor as “confused” — she hadn’t known the New Jersey arena insisted on playing the National Anthem before every concert and made a last-second decision. “I’ve often wondered if this would’ve happened if this was a man,” Sykes says. “Punk rockers and protesters often spoke out against the government and religion and did not receive this kind of negative reaction.”

After the pope-photo-tearing incident two years later, crisis management fell to Schock, who struggled to understand what O’Connor was trying to say. “It was horrible. People were trying to get me on the phone — like morning jocks,” Schock says. “Her statement was really about child abuse, but it wasn’t really explained that it was about child abuse. We had to put out a statement and said it started with the pope and the potato famine. She recommended books to read. I had to try to explain that, and I did it with her, and I don’t know if I did the best job.”

By the time Chloë Walsh came to work with O’Connor in 2005, as a publicist for her reggae-covers album Throw Down Your Arms, the singer was wary of interviews and journalists. “She never knew if people would be what she would describe as ‘f—ing horrible’ to her,” Walsh recalls. “She’d had to suffer through so many people being really angry at her and that made her very sensitive to people’s energy. She would be furtively scanning the room to check for anyone preparing to be hostile.” Just as Sykes perceived O’Connor as a truth-telling protest singer, Walsh saw her as “completely unable not to speak up if she saw something as unjust.”

O’Connor’s 1992 protest turned out to be prescient — in 2001, Pope John Paul II issued an apology for sustained sexual abuse among Catholic priests, incidents he apparently knew about as early as the 1970s but chose to protect the clergymen who were responsible. In the days after the SNL episode, and a widely televised Bob Dylan tribute two weeks later in which O’Connor’s appearance drew widespread boos, Glass, who took over as EMI president a few years after his tenure as a Chrysalis executive vp, recalls executives at O’Connor’s labels as sympathetic. “I was very disappointed with how the industry treated her. They took her off playlists and that was sad,” he says. “Of course, the industry came around: ‘She was right.’”

O’Connor never returned to her commercial peak after the SNL protest — a career downsizing, which, she explained for years, was fine with her. But her resilience has inspired generations of artists, especially women. “If you watch the [2022] documentary Nothing Compares, what really comes across is how incredibly self-restrained she is while being surrounded by an enormous amount of nauseating misogyny,” says Walsh. “Female artists today don’t have to grin and bear it when they’re infantilized by men in the industry, and a lot of that is down to Sinéad walking through the fire ahead of them.”

Chris Eggertsen contributed to this story.

https://www.billboard.com/pro/sinead-oconnor-remembered-music-executives-worked-with-her/