Enlarge / Empty traditional jars (onggi, 옹기), used for storing kimchi, gochujang, doenjang, soy sauce, and other pickled banchan (side dishes). (credit: OlkhichaAppa/CC BY-SA 3.0)

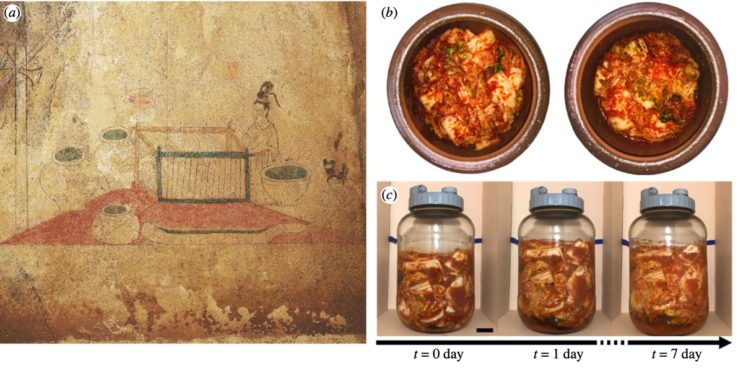

The fermented spicy cabbage known as kimchi is a staple of Korean cuisine, traditionally made in earthenware vessels known as onggi. These days most Korean households have kimchi refrigerators for that purpose, while on a commercial scale, kimchi is made via mass fermentation in glass, steel, or plastic containers. But is the kimchi made with these modern contraptions of equal quality to the traditional fermentation method? Many kimchi aficionados would argue that it is not, and now the pro-onggi faction has some science to back up that assertion.

It turns out that the porosity of the onggi’s walls help the most desired bacteria proliferate during the fermentation process, according to a recent paper published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface. “We wanted to find the ‘secret sauce’ for how onggi make kimchi taste so good,” said co-author David Hu of Georgia Tech. “So we measured how the gases evolved while kimchi fermented inside the onggi—something no one had done before.”

The handmade clay vessels known as onggi have long been used by Korean chefs to ferment foods, including ganjang (soy sauce), gochujang (red pepper paste), and doenjang (soy bean paste), as well as kimchi. The cabbage or daikon is sliced into small uniform pieces, which are coated with salt as a preservative. The salt draws out the water and inhibits the growth of many undesirable microorganisms. Then the excess water is dried and seasonings are added, often including sugar, which further serves to bind any remaining free water. Finally the brined cabbage is placed into an airtight canning jar, where it remains for the next 24 to 48 hours at room temperature. The jar is “burped” occasionally to release carbon dioxide formed during the fermentation process.

Read 8 remaining paragraphs | Comments