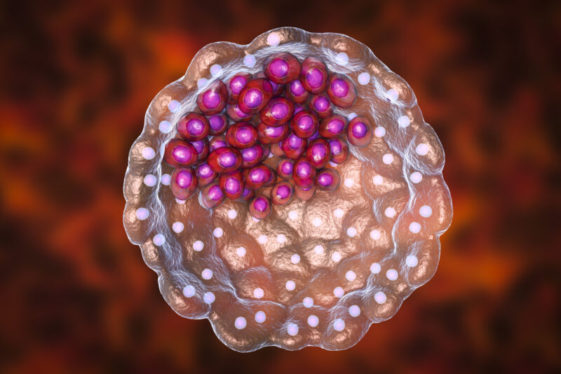

Enlarge / Computer-generated image of an early stage in embryonic development, before organ formation starts. (credit: KATERYNA KON/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY)

Scientists set a new record for growing primate embryos outside the womb, as reported in the May issue of the journal Cell. For the first time, monkey embryos were cultivated in a lab for 25 days post-fertilization, achieving key developmental landmarks never before observed in culture, including the start of organ development. The ability to track these processes in the lab might be an important step toward understanding congenital birth defects and organ development in humans.

Understanding development

The early stages of animal development, often referred to as embryogenesis, encompass the transition from a seemingly unremarkable clump of cells to a complex and compartmentalized organism. At the conclusion of embryogenesis, cells have started the march toward specialization, and organ systems have begun to form. In mammals, this is a process that usually happens in the comfort and privacy of the uterus, making it difficult to observe, even with the advent of advanced imaging. And it’s difficult to experiment with factors that might influence development.

All of this has led developmental biologists to search for ways to get this process to occur in a culture dish, bypassing these limitations. Studying human embryogenesis is restricted due to ethical and legal considerations. While the specific guidelines may vary from country to country, the outcome is a nearly global prohibition on lab-maintained human embryos past 14 days—before the progenitor of the nervous system forms. This detail is of particular medical relevance, as irregularities during nervous system formation can result in a range of conditions affecting the spine, spinal cord, and brain, including spina bifida.

Read 8 remaining paragraphs | Comments