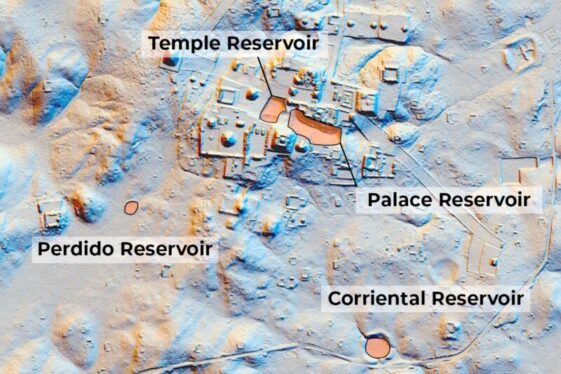

Enlarge / Lidar map of Tikal, Guatemala, showing some of its reservoirs. (credit: Image adapted Tankersley et al. 2020)

The ancient Maya city of Tikal relied on urban reservoirs to supply water during periods of drought. They essentially built “constructed wetlands” that relied upon key minerals and aquatic plants and other biota to keep the water supply potable, a “self-cleaning” approach similar to that employed in constructed wetlands today, according to a new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Most major southern lowland Maya cities emerged in areas that lacked surface water but had great agricultural soils,” said author Lisa Lucero, an anthropologist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “They compensated by constructing reservoir systems that started small and grew in size and complexity.”

Like many Maya cities, Tikal was built on top of porous limestone, which limited access to drinking water during the seasonal droughts, which typically lasted five months, although more severe droughts also occurred, particularly in the ninth century CE. So the people of Tikal relied on collecting rainwater stored in reservoirs to survive. They quarried the limestone for bricks, mortar, and plaster, all used to construct buildings on site. The resulting depressions were plastered to waterproof them as reservoirs. Eventually, the Maya built a system of canals, dams, and sluices to store and transport water. It’s estimated that Tikal’s reservoirs could hold as much as 900,000 cubic meters of water for a population of up to 80,000 people between 600 to 800 CE.

Read 9 remaining paragraphs | Comments