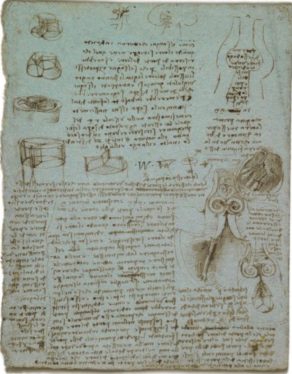

Caltech researchers recreated an experiment on gravity and acceleration that Leonardo da Vinci sketched out in his notebooks. (credit: Caltech)

Caltech engineer Mory Gharib was poring over the digitized notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci one day, looking for sketches of flow visualization to share with his graduate students for inspiration. That’s when he noticed several small sketches of triangles, whose geometry seemed to be determined by grains of sand poured out from a jar. Further investigation revealed that Leonardo was attempting to study the nature of gravity, and the little triangles were his attempt to draw an equivalence between gravity and acceleration—centuries before Albert Einstein would demonstrate this equivalence with his general theory of relativity. Gharib was even able to recreate a modern version of the experiment.

Gharib and his collaborators described their discovery in a new paper published in the journal Leonardo, noting that, by modern calculations, Leonardo’s model produced a value for the gravitational constant (G) to around 97 percent accuracy. What makes this finding even more astonishing is that Leonardo did the calculation without a means of accurate timekeeping and without the benefit of calculus, which Isaac Newton invented in order to develop his law of universal gravitation in the 1660s.

“We don’t know if [Leonardo] did further experiments or probed this question more deeply,” Gharib said. “But the fact that he was grappling with the problems in this way—in the early 1500s—demonstrates just how far ahead his thinking was.”

Read 15 remaining paragraphs | Comments