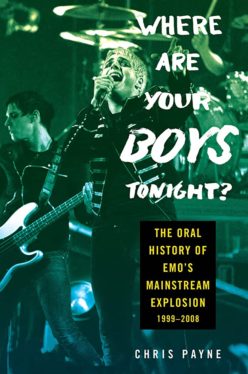

From basement shows to a Fantasy Suite at the MTV Video Music Awards, Chris Payne’s Where Are Your Boys Tonight? The Oral History of Emo’s Mainstream Explosion 1999-2008 tracks the evolution of emo’s third wave as it becomes one of the defining rock genres and youth cultures of the early 2000s.

Remembered by those who lived it from the stage, the pit and everywhere in between, Where Are Your Boys Tonight? is a vivid and breathless read that will have you reliving countless moments that you may or may not have actually lived through the first time. You’ll feel the stinging cold outside the Jersey firehouse show at the turn of the millennium, and the claustrophobic crunch inside the oversold Chicago bill in the mid-’00s, and even the social high of being at the New York celebrity scene bar in the late decade. And of course, you’ll remember the bands: countless mini-gangs assembled out of suburban desperation and an excess of teenage feelings, some with ambitions to become the biggest rock stars in the world, and some just hoping to one day play for a couple hundred fans at the local VFW hall.

While the book’s energy is intoxicating as it traverses different outposts of The Scene over the course of the decade covered — and eventually sees it go national on the radio, MTV and endless magazine covers — the spirit of it lives on in the CD and vinyl collections and Spotify and Apple Music playlists of the people who lived and loved the music at its core. It’s a story you can’t tell without its songs, whether enduring culture-shifting classics, or more forgotten gems that were nonetheless essential in the era becoming what it was. To that end, Payne has picked the 15 songs that best capture the years detailed in his book, and which best define a moment that still resonates with audiences of all ages (and even wider demographics) 15 years after it unofficially ended. (Disclosure: Payne is a former Billboard author and a longtime friend.)

Here are Payne’s picks, presented in his own words, in roughly chronological order. The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Where Are Your Boys Tonight? is out today (June 6) on Harper Collins.

1. The Get Up Kids, “Ten Minutes” (1999)

For the narrative in the book, I wanted to connect the mainstream third-wave emo stuff to the previous wave of emo. People nowadays kinda just use the blanket term “Midwest emo” to talk about all of it, even though all of it wasn’t from the Midwest. So stuff like Braid and American Football and Promise Ring. Get Up Kids, more than any of that group of bands, feels like the one that extends into the era of emo my book is about.

“Ten Minutes” is an extremely catchy, well-constructed song. And from talking to a lot of people from back then, it really did seem like there was tangible hype around the Get Up Kids being a pop band — moreso than just about any of the bands they came up with. And Something to Write Home About, that album sold about 200,000 copies in its first year for Vagrant, an independent label. It put Vagrant on the map, which would end up being like maybe the label for the first few years of my book.

This song came out in 1999 – Get Up Kids’ next album wasn’t till ’02, an album called On a Wire, and it was more of an indie-folk album. And from then on the Get Up Kids never really became the pop crossover band a lot of people thought they might be in ’99. Which I think is a lot more because of decisions they made, in not wanting to be that pop crossover band, than anything they did wrong, or miscalculated. But still, this song feels like the best pop song from the first album of this era that feels like it could’ve been a big pop album.

One of the scenes I love in the book – they’re the band that shows up with the bus at the big Jersey show, and shows everybody in the scene that this is possible. Just stepping on the bus is a big deal to all these bands, and it kinda shows you how modest the aspirations were at the time.

Yeah, it was kinda just to like play at a VFW hall, or a firehouse. But often to like 500 scene kids. So when I say “just,” it’s still like, “Damn, that’s so many people.” Which I think is really cool, and really speaks to how vibrant these scenes were. ‘Coz a show like the one you were just talking about, that was just booked by kids basically. It wasn’t like a Live Nation production. It was kids renting a PA from like, Guitar Center or something, renting out an Elks Lodge, and a couple different kids bringing a bunch of bands together who happened to be coming through New Jersey at the same time. And it just so happened that the scene was so vibrant in New Jersey at the time, so many kids were excited about it.

2. Saves the Day, “Rocks Tonic Juice Magic” (1999)

I think a big theme for my book, looking back at it, is basically just, “Hardcore bands get poppier.” That’s it. If someone wanted to be a manager and go back in time to 1999 and make a ton of money, that could’ve just been like the elevator pitch. Like, “find hardcore bands, make them cuter and poppier.”

This song is from Through Being Cool, which came out in 1999 — this is still a couple years before I was into this scene. I was 10 that year. So I really wanted to do my due diligence with talking to a lot of people, especially in Jersey, who were participating in the scene then, so I could get things right with what the setting was. And so much kept coming back to Saves the Day, Through Being Cool. There are some bands where I think, in the telling of history, it seems like they were like the first big ones – but Jersey was the biggest scene, the most important scene in this era. And for ’99, the year the book starts, the biggest band was Saves the Day.

This album is just such a lightning rod for discussion. Like, people talked so much s–t about the band having a picture of themselves on the cover, rather that just being like, some black-and-white, angry-looking hardcore album. And y’know, having the whole storyline of the band being awkward at a party, trying to talk to girls in the liner notes – very emblematic of the scene at the time. And the lyrics of this song are also very emblematic of what would be copied many, many times with bands in this scene with that genre, that sort of sub-genre of “kill your ex-girlfriend with a chainsaw”-type lyrics. So for better or worse, this album and this song really set the tone for a lot of what was to come with the genre.

You’re talking about them getting s–t for the cover – it seems like their fashion choices were maybe getting as much criticism as their pop hooks or anything. So much focus was put on them just wearing normal-person clothes.

Yeah, and I think that’s also a lot of what helped the scene get so big. Because it brought more people into the tent. They kind of just look like average high school kids. I think that for average mall kids in the suburbs, it felt more like, “Oh, this band could be me.” Versus maybe looking at like a picture of Snapcase, or Earth Crisis or something.

3. Thursday, “Understanding In a Car Crash” (2001)

So what I wanted to do a lot with this book was just see how much of the legend that’s been passed down really feels real, from talking to lots of people who actually were there. And reading about this music over the years, there’s so much of “Oh my God, when the ‘Understanding In a Car Crash’ video came on MTV” – MTV2, technically – so much of people saying, “That was the moment when the basement shows, the underground broke.” So I was thinking, “Let’s really dig into that. How true was that?”

Turns out, it was pretty damn true. As we’ll get to, there are a couple big important songs that come out in 2001. But for actually a band that came from the underground of New Jersey, from this super-now-mythologized basement scene, Thursday getting a song on MTV2 – where there is a dude in a band in shorts playing on stage in the video – that was pretty crazy. And I think it made a lot of people in the mainstream open to the idea of “heavy rock music with screaming does have a place in the mainstream.”

Some people in the book talk about the significance of Geoff Rickly’s lyrics not being “songs about girls.” Were they the first big band in this scene to kinda be like that? Were they the first to have loftier things on their mind?

Yeah, they’re not “Kill your girlfriend with a chainsaw” lyrics. Geoff, lyrically, was really influenced by DC hardcore bands – obviously Fugazi, also stuff like Q and Not U, a lot of bands that had like a deeper, more intelligent message. Also, I think Geoff came from a very bookish household. I’m pretty sure his parents named him after Geoffrey Chaucer. So that’s where he was coming from.

And kinda by accident, Thursday became the band to take that into the mainstream. Thursday wasn’t trying to be like, “OK, we’ll take singalong choruses and hardcore screaming and breakdowns and make money.” I think like their thing was more like trying to shoot for hardcore plus Joy Division. But they kinda missed the mark, and wound up accidentally with this thing that ended up accidentally connecting with a ton of people.

Rickly is such an interesting figure in this book. He’s one of the main participants as the band’s frontman, but he also can talk from a label and A&R perspective, as a producer, and he’s randomly connected to a bunch of the other figures in this story. Was he the ultimate connector figure of this moment? Did it seem that way when you were interviewing him?

Yeah, for me working on this book, Geoff Rickly was an interviewer’s dream. And I think more than any of these other bands, Thursday is the connective tissue between everything really. Between the basement scene and the major label A&R rooms, between hardcore and the poppy stuff, Thursday is the connective tissue between all of that, more than anyone else.

Do you think people realize that, give them credit for that today?

I hope so. I mean, I in a lot of ways felt like that about them when I was first getting into them back in ’03, ’04. Reading along to the lyrics of a song like “Understanding In a Car Crash,” or “For the Workforce, Drowning,” which is my favorite Thursday song — it just opens your mind in the sense of like, “S–t, almost none of the other bands in my rack of CDs are writing like this.”

4. Dashboard Confessional, “Screaming Infidelities” (2000)

Everything about Dashboard just feels so organic, looking back on this. Like, it’s been told a billion times: “Oh my God, it was crazy for a solo acoustic guy to be playing punk shows.” It was one of things that, yeah, it feels like cliché if you’ve read this stuff a lot, if you’re really into this music. But it’s like, so true.

“Screaming Infidelities” is the biggest song from that era of Dashboard, when it was just Chris Carrabba and an acoustic guitar. And it was so organic – Fiddler Records, Amy Fiddler who ran the label, she just had local distribution for stores in Florida, so she didn’t have any national distribution to get the album in Chicago or Jersey or anything. And so much of why it got big is because kids shared it on Napster after seeing him live — or not even seeing him live –- as Napster was just gathering steam.

It’s funny later in the book, after Dashboard signs to a major label and they’re trying to get Chris to film an anti-piracy ad, and he says, “I can’t do that, these are my people.” It was such a big thing at the time, trying to tamp down the filesharing, but your book makes the case that the scene couldn’t have happened the same way without it.

Yeah, the filesharing thing is like – having all this time to look back on it now, it’s obviously well-documented how it tore down profits, for a time at least, in the industry. But also artists like Dashboard, they never would’ve had a career if it wasn’t for Napster. If Napster didn’t exist, or if Dashboard had started in like ’96 instead of ’99, it probably never would’ve gone beyond being a local Florida thing.

One of my favorite scenes in the book is them going up against the Strokes for the MTV2 award in 2002 at the VMAs. It ends up being a pretty big moment with they win. Obviously, your book is gonna get compared to Meet Me in the Bathroom, because in a lot of ways, it’s sort of the mirror image: It’s what’s happening across the river, with the not-so-cool scene kids from New Jersey versus like the hipster kids from New York. And there’s fun moments in the book like this where the two scenes overlap for like a brief second. What did that moment mean – maybe not even to Dashboard themselves, but to their fans or the scene, to have them go up against each other and for Dashboard to take the award home?

Yeah, for me as a kid growing up then – I knew The Strokes were a thing, but they didn’t seem like this huge rock band. They definitely felt big in magazines. Them, and bands like Interpol and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, those early core Meet Me in the Bathroom bands – I was definitely aware of them. Probably the White Stripes felt the biggest out of all of them to me at the time. But for me and my friends and kids I knew, a band like Dashboard or Thursday or Fall Out Boy just felt so much bigger. In some ways, there’s probably metrics that back that up, and in other ways I probably was just not aware of how important The Strokes were.

But yeah, you were talking about the river as this separator — and despite how close the suburbs and New York City were, it really does feel like two different worlds in terms of what held influence. And also, some of it was bands who played all-ages shows, stuff that was accessible to kids in the suburbs, versus bands in New York City who played 18+ or 21+ shows. And also it was expensive and took a lot more time than you would think to get to a show in the city at like, Webster Hall or Mercury Lounge, if you were coming from the middle of New Jersey.

So obviously we’re going to talk about bigger hits than this, but do you think Dashboard – and maybe this song in particular – is still the image that most people have in their head when they hear the word “emo”?

I think people of a certain age. I think maybe people who were seniors in high school in ’02. To them, stuff like My Chemical Romance and Fall Out Boy is maybe something else – it’s a little too pop – and they see emo as being more in touch with punk. Which, y’know, Dashboard is.

5. Jimmy Eat World, “The Middle” (2001)

So in an early iteration of my proposal, I had it structured around starting with Jimmy Eat World. Because “The Middle” is such a huge song, obviously, the first true pop top 40 hit out of this scene. And I was like, “Oh, the narrative is so perfect – it’s a ’90s emo band, from Arizona, signed to Capitol Records, and got dropped, but had these classic albums from the ‘90s. And then they went out on their own dime and reinvented themselves. Oh yeah, this is the narrative – this makes so much sense.” And they’re like my favorite band. Bleed American was the first album I bought with my own money.

But as I was saying with the stuff that kinda predates me, I really wanted to make it authentic. And the more people from the ‘90s who were part of the scene who I talked to, the more it felt like Jimmy Eat World getting big with “The Middle” felt, like, so out of left-field. People were so psyched for them, but it felt so unexpected. Whereas where the scene really was at its core — and what people were talking about, what bands were rewriting their albums to sound more like — it was stuff like Saves the Day and Thursday. These bands were really where the core of this narrative was around ’99, 2000.

Whereas Jimmy Eat World is kind of this unexpected star that just pops in stage right, somewhere in 2002. So I tried to mirror that in my book, and have them kind of pop in from out of nowhere, out of Mesa, Arizona, about 100 pages in.

I feel like this album and song are pretty universally beloved at this point, but at the time it was savaged in Pitchfork, probably a bunch of other like-minded publications. Why do you think that Jimmy Eat World, even as one of the more thoughtful and accessible bands of that scene, were still considered Pitchfork anathema at the time?

Because they’re so earnest. Actually I do remember the first time someone showed me Pitchfork, I remember looking up Jimmy Eat World because they were my favorite band, and just being shocked that Clarity wasn’t liked. Because I was so used to that – even if someone doesn’t like Bleed American, they’d still love Clarity. That just seemed accepted. And also because pretty much all I read was punk publications back then. I totally disagree with the review – I’m pretty sure it was Ryan Schrieber who wrote it. But I think it’s a pretty funny, well-written review.

But yeah, something that was earnest was just something that was gonna ruffle feathers of that, like, 20-something city crowd. There’s a really good quote from Ian Cohen in the book, of how people thought punk “had gotten corrupted.” And I really do think that’s how a lot of the 20-something, New York City or Chicago music writers of the time felt. The fact that it was just not really tethered to politics anymore. And it was so much about the self. I think that a lot of Gen X’ers and ‘90s punk kids were pissed off about that. And also probably felt alienated and felt old, to be honest.

6. The Used, “The Taste of Ink” (2002)

Man, The Used is so important. And I didn’t really realize that until I started to work on the book. “Taste of Ink” off their self-titled album, ’02, a f–king classic album. I didn’t give it enough of a chance back when it came out. I knew “The Taste of Ink,” and I bought their second album, but I didn’t spend a ton of time with it. The first album is just like, very slickly produced, but just also so raw and gnarly. It just nails that balance.

I think the throughline of Thursday to MCR is pretty well-known at this point, as, “Thursday, the band that brought you MCR.” Which is true. But the other side of the coin in terms of the band that made MCR is The Used. Like, in talking about how it’s the third or fourth band through the door that gets big — The Used was the one right before MCR, and they did get pretty big for a couple years. Bert was dating Kelly Osbourne for half a minute, and was on The Osbournes, which was a huge show on MTV at the time. And “The Taste of Ink” was a big hit song, and the success of it I think really really opened doors to screamy post-hardcore music in the mainstream. Even moreso than Thursday.

People talk in the book about how Bert and Gerard Way from MCR had a kind of physical flirtation that wasn’t necessarily sexual, where they would kiss or hold hands in front of strangers, but they were sort of doing it as provocateurs and pushing buttons that way. There isn’t a lot of talk in the book about figures who were openly gay at the time – while a lot of these bands were adopting semi-androgynous or gender-bending aesthetics, there’s very little discussion of actual queerness. Do you think stuff like Bert and Gerard making out felt more progressive or regressive back then? And was there any real LGBTQ presence in the scene at the time?

It’s an extremely complicated question. That’s like a 10,000-word essay in and of itself. I mean, the scene was super-regressive and enforced traditional gender norms in a lot of ways. But then, like you said, you had these bands like The Used and MCR who wore makeup and definitely didn’t dress traditionally masculine. And Gerard and Bert kissing for the cameras – I mean, I don’t think it encouraged anyone to come out, at least not in large numbers, unfortunately.

Which is a shame — because I think this sort of thing, and people just seeing Gerard through the years and the figure he’s been and what he’s meant for this music, he’s definitely made this scene so much more diverse. If you see MCR live, or if you just go to When You Were Young or a festival like Adjacent Fest, it’s just obviously a very queer scene now, especially if it’s a show where MCR is playing. Which is awesome, and I think it’s honestly so much of why the scene feels still important, and still feels like it means something.

That being said, it’s strange how it was in some ways so pushing the envelope with gender and how people present themselves at the time, but also it was really homophobic. Like, I talked to Buddy Nielsen, the Senses Fail singer, for the book a lot – he’s someone in the book who didn’t come out until the 2010s. And I asked him, “Were there many people who were out in the era of the ‘00s?” And he could barely think of anyone. And he was just like, “Yeah, if I came out in like the ‘00s instead of the mid-2010s, it probably would’ve been bad for Senses Fail’s career.”

You mentioned Bert and Kelly Osbourne being a thing. It’s funny, the sort of pop crossover of some of these emo bands – it wasn’t just a radio thing, it was a visibility thing, a TMZ thing almost. You get power couples like them, and Pete Wentz and Ashlee Simpson, even Travie McCoy and Katy Perry for a minute. How much of emo’s crossover to the national consciousness was that it made for good celebrities?

I mean, it definitely has a lot of to do with why it got big in the ‘00s and not the ‘90s, you know? It’s like, Cap’n Jazz definitely weren’t dating anyone famous. Maybe if they did, then American Football would’ve gotten their due in their time.

7. Taking Back Sunday, “Cute Without the E (Cut From the Team)” (2002)

TBS just feels like high school. In a lot of ways they still do, with how many members have left that band and come into it, and the bickering over the years. And so much of Tell All Your Friends is just like, he-said, she-said, and just trashy back-and-forth. This is one of those albums that really set the tone for everything that came immediately after it. In terms of albums where, as soon as the album drops, every band in the scene is just like, “Oh s–t, the scene is going in this direction now, we gotta rewrite our next album.” When this album came out in ’02, this was the reference point for scene bands.

It’s funny, looking back at it now, a lot of these songs and this one in particular, it feels like what a lot of people now see as being regrettable about the scene – in terms of the pettiness to it, and the misogyny of it, and the baked-in kinda bad vibes to it. But it doesn’t seem like it hurts the affection that people have for this song 20 years later.

Well, the obvious reason is that the members of Taking Back Sunday were never accused of what Jesse Lacey or Brand New was accused of. I think in terms of actually crossing lines – y’know, I don’t have every lyric off the top of my head, but I think in a general way, it covers that territory of being in high school and just having like angsty emotions about dating and friends that you need to get out. Maybe it’s using some kind of violent imagery — which is not the best way to express it, and hopefully if you’re not a teenager anymore you’ve found healthier ways to express it. But I think for people that age, having music to get adolescent angst out to is just kind of a part of being 15 or whatever.

The feud between TBS and Brand New – it escalated, and de-escalated, and then escalated again – and it eventually became extremely territorial. Did it kinda buoy the entire scene to have these sort of warring factions where you could identify with one or the other? It seems like almost every major rock movement of the last 40 years has had that sort of “Oh, you’re either a this band person or you’re a that band person” struggle at its center.

I think that rivalry still has a lot to do with why people get amped up for Taking Back Sunday songs. Like, if you see them on tour this summer, I’m sure that one of the songs that goes over the best will be “No I in Team,” and that song was like written about Jesse Lacey. It was just the sort of the thing where if you were going to the show with your friend, who was just getting into the scene and heard a couple of the songs but didn’t know anything about Taking Back Sunday, you’d just be like, “Oh yeah, and there’s this other band from Long Island who’s starting to get popular called Brand New, and this song – let me play it for you – this song is about the singer…”

So immediately there’s a narrative, there’s a hook that draws you in, other than just, “Oh, here’s an album, the songs are good.” Narrative is always so important with pulling people into music. And this one definitely has unsavory parts to it, and parts that are pretty corny in retrospect. But the rivalry was very real, definitely for a few years in the early ‘00s.

8. Brand New, “Okay I Believe You, But My Tommy Gun Don’t” (2003)

The way I approached Brand New in the book, I laid it all out in the opening of the book – where I say, “I aimed to show where and how Brand New drove the narrative of emo getting huge without glorifying Jesse Lacey himself.” And I said what the accusations were against him. It’s the sort of thing where, if I was writing a list for a website of the best songs of an era, I probably wouldn’t give space to Brand New at this point in time. Because why glorify him more? But for writing the book, there’s no way that you could tell this narrative without talking about Brand New and talking about their influence. Especially since it’s an oral history.

Their appeal is so cultish and specific that it’s hard to put into words. And for me, this song captures that the most. It’s so lyric-driven for so much of the song. The first two minutes or so, it’s just a very, very sparse song with just a little bit of guitar, barely any percussion… and this would be such a moment in a live show, of kids singing along and eating this s—t up. I feel like it must be so weird to decipher if you weren’t around it. Because it’s just like, “Is this dude real with this? Is he really saying, ‘I am heaven sent, don’t you dare forget’?”

For me and how I feel about this – I loved Brand New. I remember for some blog I did a ranking of albums from bands in this scene, and I think it was in 2014, 2015, and I put Deja Entendu at No. 1. So that’s where I’m coming from with this. But if Brand New was to get back together now, I’m not going to that show.

How much of it with Deja Entendu and the unique place that this album holds with fans of this moment is that like, it was about as big as it could get without really crossing over? It feels like an iconic release of its time period, but there were no real hits off the album, it didn’t make it into that larger consciousness – Jesse Lacey wasn’t a pop star – does it feel like kind of the biggest thing that emo kids can still say is entirely theirs?

Yeah. Like, “As big as you could get in the scene without crossing over” really does feel like an apt way of describing it. And I think a lot of that is why scene kids, even into the 2010s – hopefully ending with the allegations coming out – why kids owned this music so closed to them. Because it still felt like it was theirs. Whereas a band like Fall Out Boy or MCR crossed over into pop stardom, Brand New never did. Yet the second they announced a tour, it would sell out.

You know, with the book – another thing that I write, is that I truly hope that this book brings no further pain to those who were hurt by Jesse Lacey. Brand New, to tell the narrative, had to be included. But I just hope that I brought no further pain into anyone’s life.

I’m sure they’re still very regularly played at emo nights, and during big group moments of nostalgia in general. Do you think there’s been any kind of reckoning with people’s relationships with Brand New, when it comes to the average fan? Is there a different vibe to it now when those singalong moments happen? Or is it, “No, these were the anthems of our youth and we don’t want to put that extra weight onto them?”

For me, when that stuff comes on in like a very public setting, I’m not into it. I think unfortunately, a lot of people either don’t care or just don’t really know. I think working in the music industry, it’s easy to forget how a lot of people’s experience with music is just streaming it on Spotify. And these people aren’t reading Wikipedia or keeping up with news or even keeping up with much of anything specific about the artist. Probably a lot of people, the songs off Deja are the songs that pop up sometimes on emo playlists on Spotify. And probably a lot of people aren’t even aware of the Jesse Lacey situation.

9. Fall Out Boy, “Sugar, We’re Goin Down” (2005)

I think they basically took the hardcore thing I was talking about earlier – with making hardcore pop – they basically took it as far as you could go and still have it be hardcore music. Beyond “Sugar, We’re Goin Down,” it had to go someplace else. They took it as far as it could go in that direction. And Fall Out Boy did go someplace else, with Infinity on High. But I just remember thinking it was so cool back then to be like, “Wow, this is like a hardcore song that you can pit to – but it’s on Z100 constantly.” And it was like, “Yo, this is the breakdown right here, this is the really heavy part, it’s actually kinda secretly heavy… that’s so crazy that this is actually on Z100, not just a little bit, but like, a lot.”

Pete Wentz is a figure in your book going back to the mid-‘90s, in Racetraitor in Chicago. Was Fall Out Boy’s success just a matter of Wentz meeting someone in Patrick Stump who had the sort of vocal talent to execute his vision?

Patrick’s so important. Yeah. There’s this – it’s so funny how extravagant Pete is when he talks about these things. There’s a quote in the book where Pete’s like, “Before I met Patrick, I felt like a painter staring at a blank canvas, but all I could do is fingerpaint, and then I met Patrick and he showed me the way…” But it’s true, because like – Pete had the vision, Pete was already a minor celebrity within hardcore. But Pete’s not really a singer. He’s a good frontman as a hardcore frontman, screaming, but he’s not a singer. And he’s a really good lyricist. So like so many bands or creative successes, it’s a partnership of two. And that’s what Stump and Wentz are — they were completely interlocking, symbiotic, filled in the other sides and that was it. They were the perfect duo.

It’s funny how the VMAs keep popping up throughout your book – it’s kind of the stand-in for all industry award shows and acceptance – but they’re up for the MTV2 award in 2005 against My Chemical Romance. And they win, and it’s surprising to a lot of people, but they go up and thank MCR as part of it. And there’s an Andy Greenwald quote in the book about the two bands being sorta together, but also sorta not together – using themselves as measuring sticks for one another. What do you see as being the dynamic between those bands as they sorta become the defining bands of emo in the mid-‘00s?

Well, also in that part, Andy says like, “This was a time when their agendas lined up.” Which I think is a very good way of putting it. I mean, Fall Out Boy winning that award and shouting out MCR was super indicative of like, the scene vibe back then. Where it was all, “Support the scene!” And a lot of that is earnest, you know? The scene was in a lot of ways this insular thing – which got really popular, but still it’s this insular thing, this counter-culture club that somehow just got way bigger than anyone thought. And part of the ethos of it was shouting out the other bands, singing their praises.

This was one of the genres where it’s kinda common to see artists performing, but wearing a band tee of another artist. Where the vibe is like, “Yeah, my band’s cool, but so is this other band.” And y’know, I think MCR getting shouted out by Fall Out Boy is like a good example of this. And I think at this moment in time, the bands are definitely friendly. Would be pretty sick to see them go on tour together. Logistically, I don’t know if that would really be feasible. Because they’re both big, but in pretty different ways. Which is I think why they were so fascinating to me as co-leads for the book.

The ultimate perfect ‘00s emo-pop crossover single: “Sugar, We’re Goin Down” or “The Middle”?

I mean, “The Middle” changed my life so much. I can’t say anything but “The Middle.”

10. Panic! At the Disco, “Time to Dance” (2005)

So I know probably the masses by now see “I Write Sins Not Tragedies” as The Big Panic Song, at least on A Fever You Can’t Sweat Out, their debut album. But – real ones know – this was the first song that made waves on the internet. It was “Time to Dance.” “I Write Sins” wasn’t available until the album actually came out. “Time to Dance” was the first demo of Panic!’s that was out online, once Wentz started to hype them up. It was the song that started it all for them. And if you saw them in that era, this absolutely would’ve gotten one of the best responses of anything on that album.

In a lot of ways, just having lived through all these years, this era of Panic! feels so cool and unique to me. Because to me, it feels like the first superstar artist that purely came from the internet. Fever feels like that album, and the first thing that hit from that is “Time to Dance.”

The other interesting thing, which sorta goes hand in hand with this – someone talks in your book about how Panic! were sort of the first band of this moment that wasn’t thinking at all about, “How are we gonna play these songs live?” Because they didn’t really do the coming up through the scene, paying their dues live stuff. So they were able to think bigger about these songs, kinda envision them in ways that wouldn’t necessarily have been translatable live – beat switches, extra instrumentation, not the sort of thing that four guys in a small venue can necessarily recreate on their own. But it makes the songs – and this one in particular – feel very expansive musically.

Yeah, this album, and just Panic! as a thing getting big pissed off so many people back then. I mean, because they had never toured really before, and they got signed and got immediately huge, and didn’t “pay their dues” – because they played live with a lot of backing tracks, ‘coz there was all this extra instrumentation on the album – they were super-polarizing. Everyone had an opinion on them. They were just like a lightning rod for everything.

But they seem super-ahead of their time now.

Kinda by accident. Because I don’t think they made the album being like, “We need to make backing tracks accepted in the scene – the scene’s been against extra instrumentation live for far too long, we need to normalize backing tracks!” I don’t think that was the intent. The intent was they didn’t know any better, because they had never toured before. And because GarageBand had just come out on the new MacBooks, that gave them the basic technology to make these songs that previously you would’ve basically needed your own human garage band of people performing in a garage to do that.

Do you think the role in the original vision of the band that Ryan Ross played — does that kind of get lost to history now that Panic! is just mostly Brendan Urie?

Oh, totally. And I like really tried to emphasize Ryan Ross’ importance in the book. Because Ross was the principal lyricist for Fever, and a lot of it was like really personal lyrics about his tumultuous relationship with his dad, and his dad’s struggles with addiction. Being a fan of the band back then, it definitely felt like much more of a band. Like, Brendon Urie was famous to a degree, because he was the singer, but you kinda knew like… all their names? I remember it was such a big deal when Brent, the original bassist, got kicked out of the band. So the Fever era of Panic! was definitely a group effort, and Ryan Ross as the principal lyricist, and a huge collaborator with Brendon … you can’t underestimate Ryan’s importance.

11. My Chemical Romance, “Welcome to the Black Parade” (2006)

In a lot of ways, Black Parade feels like the consummation of everything with this book. MCR basically took it as far as you could, you know? Like, the most ambitious album really that you could really conceive from a band of their ilk. And they nailed it. This was the song that finally got your typical classic rock fan, emo hater, to be like, “You know what? MCR, they’re all right, because they’ve got this rock opera and it reminds me of Queen, and Rolling Stone tells me it’s OK.”

But then it’s like – what comes after that? Nothing. It’s hard to think of any bands that really even tried to imitate it or rip it off, because it was like so untouchable. It was like, “How do you even try to rip it off?”

One of my favorite recurring themes in your book is other artists talking about My Chemical Romance and saying, like, “We thought we were pretty good, we thought our album was tight, and then we heard Three Cheers or we heard Black Parade and we were like, ‘Ah, f—k. They got us beat.’”

Yeah, some good quotes from Taking Back Sunday about that in the book. So yeah, I’m sure it definitely made some bands jealous when it came out. But it’s hard to think of anyone who even sonically, aesthetically, tried to imitate it. And definitely no one topped it.

I think that like with the next wave of emo, like the revival stuff, it kinda makes sense now, looking back that a lot of that stuff started popping up in ’07, ’08, ’09, the immediate years following Black Parade. Not because it was really influenced by Black Parade, but just because the emo mainstream thing — if you’re an ambitious musician who’s really interested in this stuff, where do you go next? I would imagine by ’07, you’re not really thinking about one-upping Gerard Way or Pete Wentz. This was around the time that people were starting to discover or re-discover American Football, like, “Let’s do those twinkle riffs and see how far we can take that.”

Seems more achievable, maybe.

I think also a lot of musicians were more interested in something where it felt like they could touch it. That felt a little bit more accessible, more communal. Not that Black Parade isn’t, but y’know, something that them and their friends could maybe pull off in a house show.

When people look back at emo 30 years from now, do you think that Black Parade is gonna be the first album they think of?

Yeah. I would say so. I mean, it is now. Even if it’s not your favorite album of the era, it’s kind of hard to argue against it being the pinnacle of the era, for emo’s mainstream moment.

12. Paramore, “Misery Business” (2007)

I was just talking about how it felt like everything was over in a way after Black Parade, like, “Yep, they took emo-pop as far as you could, that’s it, then it went underground.” Then in ’06, there was Paramore – they were a big band, but they were also as big as you could be in the scene, without being big outside of it. It’s funny to think of how in ’06, Paramore and this other band Cute Is What We Aim For were both on Fueled by Ramen, and were probably both equal-sized bands. Did not last for too much longer.

When Riot first got announced — I’m not sure if I saw the album art first, or heard “Misery Business” — but I just remember being like, “Yes, obviously.” Because everyone kind of figured the band would be huge, it was just a matter of when. The first time I saw them was behind All We Know Is Falling, the first album. And I remember there were like, middle-school-aged kids at the show. Which you saw a little bit of back then, but the fanbase was even younger. And they had lyrics printed out with them — kids bringing the printed-out lyrics to sing. And it spoke to how much of a different fanbase the band was tapping into: younger kids, and obviously, young women.

Because going to shows back then – it was totally commonplace for half the crowd, or more than half the crowd, to be young women. Girls are such a reason why the scene got as big as it did, and it’s pretty ridiculous — confounding, even — to think of why there wasn’t a big female superstar in that scene until Paramore.

Not even just a superstar – this is the 13th song we’re talking about, and Hayley Williams is the first woman of any kind we’re talking about, at least as a performer. Are you of the opinion that these female-fronted bands, or these women in bands were out there, but they weren’t getting the support either from the scene or from the labels or even the fans that their male counterparts were? Or do you think they were sort of discouraged by the fact that the scene was so male-dominated, and that there weren’t even that many girls in bands trying in the first place? If women were so well-represented in the audience, why were so few making it on stage?

I still don’t really have the answer to that. If you try to like, think of the source of this, and think about the early slot bands on like a festival like Bamboozle or Warped, or the baby bands getting signed to a big scene label like Victory or Fueled by Ramen… there just wasn’t much female presence to any of it. So it sucks, but I just don’t remember that many women in bands back then, before Paramore. I just don’t.

It wasn’t only endemic to emo. If you look at the three biggest rock moments of the ‘00s, between emo, nu-metal and the new rock revolution, they all have exactly one female-fronted band in their sort of A-tier. So was that just kind of 2000s rock in general, and maybe emo gets more focus for It because of the lyrical focuses of those bands, and some of their offstage problematic behavior?

I think it also rightfully gets some of the extra focus because emo was so intertwined with hardcore, and you can trace it all the way back to Ian MacKaye and Revolution Summer and progressive leftist social issues. Which is why I think it’s fair – we should hold all genres to scrutiny for this, obviously, but I think it’s fair to hold a little extra scrutiny to emo. Because if you trace the genre back, it was professing to be inclusive.

Just to go back to “Misery Business” – I’m curious what you think the scene-y, more real-head fans of Paramore think of this song. Obviously the band has a pretty complicated relationship with it – Hayley even said they were going to stop playing it, at least for a while – because it has some regressive gender dynamics. And I also just don’t think it’s a song that really demonstrates what’s great about the band, at least compared to some of the other songs on this album and later hits of theirs. But it is still a towering part of their catalog. Is that the true fan take on it too, or do they have a mixed relationship with it?

A lot of Paramore fans I think definitely have like a mixed relationship with it, because of what you were saying with Hayley’s evolution with her relationship to the lyrics over the years. From what I’ve observed, the most common fan favorite song from this album seems to be “That’s What You Get.” My favorite is “CrushCrushCrush.” But I still think “Misery Business” is one of the three or four strongest songs on the album. And what I was saying earlier about MCR and Black Parade, I don’t think Riot necessarily took the genre sonically to like new territory. But it’s an exceptional rock album from a voice that the scene desperately needed.

13. Underoath, “A Boy Brushed Red Living in Black and White” (2004)

So with the book, I really wanted to shine a light on elements of this scene that I felt were kind of lost to the cracks of history. And one of the biggest ones was how much of a Christian thing this scene was. It was so common to hear bands say, “We’re not a Christian band, but we are Christians in a band. Our faith is really important to us.” Back then, it was kind of just like, “Well, some bands in the scene are straight edge, some are vegan — oh, this band is Christian.” It was just one of those things, one of those classifiers, for a band that came up in emo or post-hardcore.

Underoath were representative of just a massive contingent of Christian and pseudo-Christian bands in this scene. Which Paramore was part of in this era. Paramore loved Underoath. They were a huge influence on their debut, All We Know Is Falling. And Paramore, especially the Farro brothers, especially Josh, were very much of the “Christians in a Band” category.

When you talk of Underoath’s fans, were they mostly also fans of the band for their sort of devout Christianity? Or was that sort of incidental to the package, and maybe a lot of them didn’t even really realize about it?

It was a mix. And some people – there definitely were like youth group kids, who will say like, “Oh, I love the Underoath and Norma Jean and Emory and Mewithoutyou, because I wanted to be into this music but the Christian bands were all my parents would let me listen to!” So there was those youth group kids, and then there were kids who had no idea who just loved it because it was like heavy music that sounded really like of the time.

There is a song – the last song on this album was written by the singer of a band called Copeland, or co-written, where they sing about Jesus by name, and it’s obvious. But aside from that, no one I don’t think would ever decipher it.

One of the funniest parts of your book – and it’s sad in a way, too – is the antagonistic relationship they have with Fat Mike of NOFX. Your book has some great sort of incidental villains, and Fat Mike kinda comes off as this sort of relic from another era, who doesn’t totally get what is going on with these bands, but is sorta forced to interact with them because they’re coming from different parts of the punk universe. And he makes a crack about one of the band members on stage that maybe breaks up the band for a minute?

[Laughs.] Yeah. That was one of those things – that Fat Mike/Underoath thing – where if you were like a scene kid reading AbsolutePunk and Alternative Press every day, this was such a thing. It’s forgotten now, but it really meant a lot to me to highlight these things. It was such a thing back then, and it was so emblematic of this era, of the scene bands – the Fall Out Boy/MCR wave of stuff – being huge on Warped Tour. Huge in general, but Warped Tour was pretty much the venue where these worlds would crash. Like, the ‘90s skate punk bands — where Fat Mike was the royalty of that crowd — coming together with this younger generation that was getting way bigger than them on Warped Tour, and often drawing way bigger crowds. In ’06, Warped Tour was coming off its biggest year, where Fall Out Boy and MCR kinda overtook everything. So Kevin Lyman kind of wanted to book a lot more punk bands, and inadvertently, one of them almost ended Underoath.

It was kind of this forced crossover in this space like Warped. Because otherwise, bands like Underoath and bands like NOFX would’ve both been on the Warped Tour comp CD, or they both would’ve been covered in Alternative Press, but there was little to no overlap in their fanbase. Almost all of my friends who were into this music liked Underoath, but I didn’t know anyone growing up who listened to NOFX.

14. Gym Class Heroes, “Cupid’s Chokehold” (2005)

This song was huge. Got huge in a really unlikely way. It was on their album The Papercut Chronicles, which basically sounds like The Roots but emo. It came out just before Fall Out Boy became superstars, in early ’05. And then it was one of those things where the scene gets bigger, Fall Out Boy –who had discovered and put on Gym Class Heroes — they get way bigger. So there’s a bigger platform for their follow-up album. But it’s this old song that catches on with radio.

It’s a very 2023 story, actually…

Yeah, there’s a lot of parallels to now with how big “Cupid’s Chokehold” got. It probably peaked in popularity two years, two-and-a-half years after it came out, but it was already the next album cycle. So it’s like this old song from a prior album usurping the lead single from the new album, which was supposed to be the big one.

Gym Class Heroes probably has better songs – “Taxi Driver” is the one I would shout out, the Gym Class Heroes’ true MySpace phenomenon song. But this song was huge, and I think it’s a pretty cool thing in retrospect, how there was a Black rapper fronting a band in this world that was still at this point super-white. Aside from Wentz, there wasn’t much interaction with the hip-hop world. And just how big this song got, for a few years how huge Gym Class Heroes were, coming out of this scene was pretty cool.

You talk about the audience being split pretty evenly in terms of gender by this point in emo history – it probably was still majority white in terms of the audiences. But there were Black emo fans, and you even interview some of the higher-profile ones in your book. Does that part of the emo scene get overlooked, or was it really that small a minority at the time?

I mean unfortunately, it was still pretty white. Fortunately it’s gotten a little bit more diverse since, but back then it was an extremely white scene. I definitely think Gym Class Heroes opened people’s minds to more things. I remember seeing my buddy Greg’s band open for Gym Class at the Stone Pony in like ’05. And I remember Travie being like – I’m paraphrasing here — “Raise your hand if you don’t really vibe with today’s hip-hop music!” I think what he was getting at was his band had a more indie approach, kind of a backpack rapper-y thing. And he probably just figured a lot of the kids, like, were not up on what was going on with rap at the time. Which is probably true.

But I think he did a good job of probably pushing some kids to push out some more rap music. I mean, he definitely made me a little bit more interested. I was still just largely listening to nothing but scene bands, but I bought Papercut Chronicles. And now that I think about it, that probably was the first rap CD that I bought.

15. Fall Out Boy, “What a Catch, Donnie” (2008)

So this is sort of the big closing number for the emo decade, I guess?

Yeah, and talking to some of the people like Gabe Saporta, who guested on the song, and Alex DeLeon of this band The Cab – it definitely felt like that, they told me, at the time. The writing was kind of on the wall that this was going to be the last Fall Out Boy album, at least for a while. And yeah, it’s pretty on the nose for them to write a song like this and include It on the album.

Having guest parts in the big closing part of the song from across the Pete Wentz circle and Decaydance records sing little bits of old Fall Out Boy songs in succession, tracing their star… the song that William Beckett from The Academy Is sings is a song called “Growing Up,” which even predates Take This to Your Grave, so they go way back. And with Folie a Deux being kinda misunderstood when it came out – and not being a huge flop, but being enough of a flop to halt Fall Out Boy’s upward trajectory – it definitely seems a parallel to the scene in general, by the time we get to 2008. Things weren’t on the upswing anymore, and were kind of petering out.

Was this always going to be the endpoint, at this certain moment in time? If Folie a Deux had been different, if things had broken different for one or two of these other bands, do you think that emo could’ve kept its relevance into the most decade, in that sort of form? Or was its time in the spotlight sorta destined to end when it did?

Yeah I think so. Because you even have through this era, through the tail end of the ‘00s into the 2010s – Paramore were still huge, they had a couple of their biggest hits. Panic! were still together. And some other bands like Cobra Starship and Gym Class had some of their biggest hits.

Most of those bands are getting away from emo at that point, though. None of those bands really still sound like emo by the time they score this big hits.

Yeah, but they were still bands that had their roots, and a lot of their fanbase was whatever the 2009 or early 2010s version of scene kids were. So there were still some bands of that world who were really successful. But still, it felt like emo as a culture, as a movement, was not in the mainstream anymore. Even with the pop hits going for it, no matter what, it had kind of run its course as like the defining cool youth culture. Well, I don’t know about cool, but… as a defining youth culture of the time.

I think this was a time when EDM, for young kids, kinda took over that territory in some ways. And as far as rock music goes, indie rock and blog stuff took over some of the other territory. And then I think a lot of it is like, kids get older. Some kids just don’t find a big new music thing — they just get really into, like, their job. Or gaming. Or just something else, you know?

If you could include one more song on this list that’s sort of from outside of the timeline of your book, from 2009 to present. What would be the one song, or some of the primary contenders for songs that keep the emo flame burning in the years since?

Hmm. It’s that Lil Peep song that goes like, [sings] “Cocaine, switchblades… GothBoiClique make…” That song. But yeah, I think a lot of what – aside of MCR getting back together, and the legacies of these big bands, I think a lot of what makes this music still feel relevant, interesting, a space for not just nostalgia but also artistic growth now, is stuff like GothBoiClique – especially Lil Peep, because he was by far the biggest of that group.

So the scene kids would’ve been into Lil Peep?

Yeah, exactly. Like, the mid-2010s version of what like an MCR superfan who just got into them ‘coz of like the “Helena” video in ’05 — 10 years later, that kid would’ve been at one of those Lil Peep shows.

Stories about sexual assault allegations can be traumatizing for survivors of sexual assault. If you or anyone you know needs support, you can reach out to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN). The organization provides free, confidential support to sexual assault victims. Call RAINN’s National Sexual Assault Hotline (800.656.HOPE) or visit the anti-sexual violence organization’s website for more information.