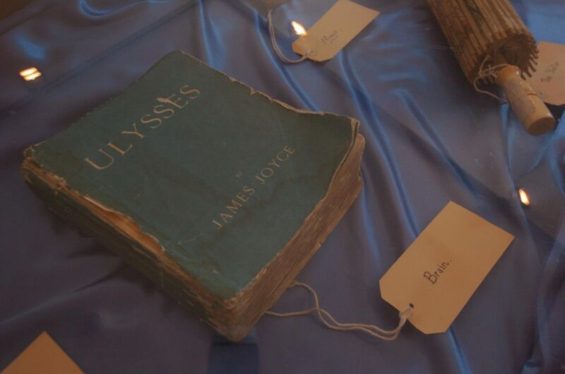

Enlarge / An early edition of one of Dublin’s most famous literary masterpieces: Ulysses by James Joyce, published in 1922. (credit: Fran Caffrey/AFP/Getty Images)

Ulysses, the groundbreaking modernist novel by James Joyce, marked its 100-year anniversary last year; it was first published on February 2, 1922. The poet T.S Eliot declared the novel to be “the most important expression which the present age has found,” and Ulysses has accumulated many other fans in the ages since. Count Harry Manos, an English professor at Los Angeles City College, among those fans. Manos is also a fan of physics—so much so, that he penned a December 2021 paper published in The Physics Teacher, detailing how Joyce had sprinkled multiple examples of classical physics throughout the novel.

“The fact that Ulysses contains so much classical physics should not be surprising,” Manos wrote. “Joyce’s friend Eugene Jolas observed: ‘the range of subjects he [Joyce] enjoyed discussing was a wide one … [including] certain sciences, particularly physics, geometry, and mathematics.’ Knowing physics can enhance everyone’s understanding of this novel and enrich its entertainment value. Ulysses exemplifies what physics students (science and non-science majors) and physics teachers should realize, namely, physics and literature are not mutually exclusive.”

Ulysses chronicles the life of an ordinary Dublin man named Leopold Bloom over the course of a single day: June 16, 1904 (now celebrated around the world as Bloomsday). While the novel might appear to be unstructured and chaotic, Joyce modeled his narrative on Homer’s epic poem the Odyssey; its 18 “episodes” loosely correspond to the 24 books in Homer’s epic. Bloom represents Odysseus; his wife Molly Bloom corresponds to Penelope; and aspiring writer Stephen Daedalus—the main character of Joyce’s semi-autobiographical A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916)—represents Telemachus, son of Odysseus and Penelope.

Read 9 remaining paragraphs | Comments